Steve Albini nous explique pourquoi Believe de Cher est la pire chanson jamais enregistrée

Steve Albini sur les trends cancer dans la pop. Ca parle de Farrah Fawcett et de dubstep, aussi.

Ca se passe sur The A.V. Club pour leur rubrique "hatesongs" et on leur est gré d'avoir posé la question.

Steve Albini: As a recording engineer—someone who is deeply embroiled in the process of making records every day—you see trends and fads run through the social organization of the population of musicians in the same way that they would run through a high school. I’m going to date myself, but in the late ’70s, when I was in high school, there came a rash of women wearing Farrah Fawcett hair and having very large-handled combs in the back pockets of their pants. They would wear Levis of various colors or other jeans, but sticking up out of the back pocket of almost every single one of them was a very large plastic comb. And most of the girls at my high school had this feathered Farrah Fawcett hair.

Steve Albini: As a recording engineer—someone who is deeply embroiled in the process of making records every day—you see trends and fads run through the social organization of the population of musicians in the same way that they would run through a high school. I’m going to date myself, but in the late ’70s, when I was in high school, there came a rash of women wearing Farrah Fawcett hair and having very large-handled combs in the back pockets of their pants. They would wear Levis of various colors or other jeans, but sticking up out of the back pocket of almost every single one of them was a very large plastic comb. And most of the girls at my high school had this feathered Farrah Fawcett hair.

So you see that happen in a way. Two years ago, no one had a big comb and Farrah Fawcett hair; this year, everyone did. There was also a particular brand of lip gloss called Bonne Bell Lip Smackers that were typically worn on a lanyard around the neck of the girl, I guess so it would be available for immediate reapplication should any lip de-glossing occur. All this stuff happened at the same time in the late ’70s.

You see something happen to a population whereby everyone adopts something that’s just preposterous in a way that makes it normal instantly. If any one person prior to the rash of puka shells, for example, was seen wearing puka shells, he would look like an idiot. But when everyone is wearing them, it instantly makes them normal.

So I’m kind of sensitive to that stuff happening in recordings, and it happens a lot with recordings when there’s a technological advance, like in the ’80s, when drum machines became really prominent in production. A lot of albums were made where, even if it was a band that had a drummer, the drummer didn’t appear on the record, because the drum machine was just so much more reliable in the mind of the producer or the engineer or whatever. You had all these bands whose drummer was just surreptitiously or even openly replaced by a drum machine. That sort of standardized the production aesthetic for a few years there. Everybody from Pat Benatar to Martha And The Muffins to Frankie Goes To Hollywood—there was a period when their drummers weren’t allowed to appear on records. Even hard-rock bands. I don’t want to name any examples, because I’ll probably be wrong in the specifics, but in the hair-metal era, you’d hear a lot of heavily produced synthetic drum sounds.

Those things are kind of grating if you’re aware of the area behind the curtain in Oz, and you see this happen. Whoever has that done to their record, you just know that they are marking that record for obsolescence. They’re gluing the record’s feet to the floor of a certain era and making it so it will eventually be considered stupid.

There are a lot of things that fall into these categories. One of them that happened in the late ’80s and early ’90s was the appropriation of African pop as a motif in conventional Western pop music. Peter Gabriel and David Byrne were quite responsible for that. But you saw it working its way through that stratum of rock stars. Like, “Hmm, maybe we should have an African part?”

There were certain other production gimmicks, which are especially annoying to me because I know that they could not come from a band in rehearsal. No band in rehearsal just decides to do what the Dust Brothers did on every record, where it sort of zoomed in on a loop and then went back to a new mix. The song is going along normally, and then suddenly it’s over the telephone, and there’s a little dumb loop in it.

There’s the supernova moment where a cliché like that doesn’t exist, and then suddenly it does, and you just know it’s going to run like a rash through music and really bum you out. I don’t listen to a lot of pop music, so I’m not that conscious of what’s going on in the contemporary world. But once in a while, a song out there in the mainstream pop world develops some appeal within my peer group—which is the rock-band and abstract-music people—and for some reason, they latch on to some piece-of-shit pop song that they can listen to ironically, or listen to as a guilty pleasure, or sometimes just listen to outright.

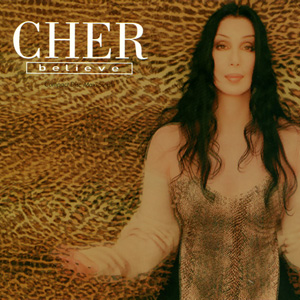

“Believe” is this horrible dance-pop song that Cher did in one of her many vampire-rising-from-its-own-ashes moments that she’s had so frequently in her career. It had one of these synthetic moments that I could tell instantly, that was going to be the go-to gimmick for everyone who was stuck for an idea. And that was the synthesized, pitch-modulated vocals that she used in the song “Believe.” As soon as I was aware of that, I realized, “Oh yeah, you know that thing with Auto-Tune that people thought they were getting away with for the last few years? Here’s their excuse to use it baldly and brazenly and not care if anyone notices.” All those people who had been sneaking the odd note into Auto-Tune to try to hide the fact that they were bad singers, now they could embrace the fact that they were bad singers. That seemed inevitable, but when it finally happened, it seemed really depressing to me.

A bunch of my friends, for whatever reason, decided they wanted to entertain that song as an interesting piece of music. You’d run into people you liked and the “Believe” song would come on in the bar, and instantly, the conversations would stop, and they would start talking about how they actually liked that song. They actually liked the dumb vocal thing. It happened over and over again, just really cringe-worthy moments. It’s like in a zombie film, when you see your friend has been bitten and you’re just looking for the cues that he’s going to go full zombie on you. It was that sort of thing. One by one, I could see that my friends had gone zombie. This horrible piece of music with this ugly soon-to-be cliché was now being discussed as something that was awesome. It made my heart fall.

Probably the most depressing moment was when bands would start to cover that song, and sometimes they would do it with the vocal effect, and sometimes not, I guess as a way of validating the song, devoid of the cliché, maybe? But all the covers, like Bedhead Loved Macha’s, just made me embarrassed for those bands.

The A.V. Club: Did you tell the Kadane brothers, who were in Bedhead, when you worked with them on the last New Year record?

SA: It hasn’t come up. [Laughs.] I think they know my distaste for that song. So it hasn’t come up. They certainly aren’t looking for validation from me about what they do with their band.

But it was just a depressing period. To see people getting in line with the fucking Farrah hair and the pink comb and the Bonne Bell—it was really depressing.

AVC: There’s no real myth behind “Believe.” Everyone knew from the outset that it was a studio creation. It has six different songwriters and three different producers, and it was recorded over something like 10 days.

SA: You can tell they were stuck. They were looking for a way to fix that glitch so Cher would sound like she was in tune. They obviously had the audio effect out just in case, and somebody overdid it and was like, “Okay, well, let’s see if we can make that the hook.”

AVC: Do you ever have people come in to work with you and say, “Hey, can we do this?” meaning something like Auto-Tune that you would absolutely not want to do? Or do people who come to you generally know what they’re getting?

SA: Like anything else, I get asked to do it occasionally. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, there was a slightly retro drum sound that was popular in hip-hop music called the 808 bass drum sound. It was the bass drum sound on the 808 drum machine, and it’s very deep and very resonant, and was used as the backbone as a lot of classic hip-hop tracks. Rock bands would occasionally ask, “Hey, can you do the 808 bass drum thing there?” As an engineer, your job is to have solutions for people when they want to try stuff. So almost every engineer in the ’90s developed a technique for either simulating or acquiring the 808 bass drum sound for that one moment in the song where the band wanted it to happen.

AVC: Have you had any bands ask you to pump up the dubstep on their tracks?

SA: [Laughs.] “Can you just turn the switch and have Skrillex happen right here?” I mean, obviously, whatever the band wants to do, they get to do. It’s not my job to talk them out of anything. But there are clichés that come from all eras.

There is a particularly swirly phaser sound that Small Faces used on the song “Itchycoo Park” that was a very deep resonant sound, and after that, an awful lot of people tried to incorporate that phaser sound into their record—some to good effect, and some to bad effect. But that was such a cumbersome thing to do that it wasn’t instantly adopted. Cranking the Auto-Tune is so easy to do that there’s almost no systemic resistance to trying it. So when someone’s stuck for an idea, that’s what they do. I mean, to the extent that it’s been embraced by an entire idiom of club music and culture.

I can’t really say I ever hear it. It has moved out of the novelty phase where it was infecting my friends and their choice in music, and now it’s just affecting an entire idiom of music that I never hear. I never hear club music. And the kind of synthesized R&B music that it’s also popular in, I don’t ever hear that either. It doesn’t cross my path very much, and it’s unlikely that I will ever be offended by that sound again, because it has graduated and moved up the food chain from the early adopters to the pack lexicon. In the same way I’m never going to see prop comedy, or a guitar-comedy act, I’m probably never going to be offended by Auto-Tuning anymore.

AVC: There are several different angles you could have come at hating “Believe” from, but the one you picked is pretty interesting. It’s not just, “Well, this song sucks, because Cher sucks.”

SA: It’s not just a terrible song. There are a million terrible songs. The world is crawling with a million terrible songs. But when it’s a terrible song that gives all your friends brain cancer and makes shit foam up out of their mouths, that’s when it’s a problem. Otherwise I can just totally ignore all this stuff.